Learn more about the U.S. - Mexican War. Explore Freedom's Way National Heritage Area. |

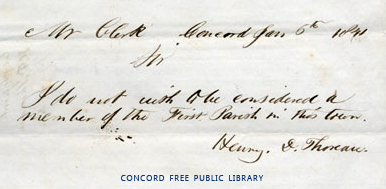

Concord JailIn July 1846, just over a year into his sojourn in Walden Woods, Thoreau was walking into town when he was arrested and taken to jail by Sam Staples, Concord's constable and tax collector, for failure to pay his poll tax. He mentioned the incident in his first book, A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, which he was drafting at the time. "While the law holds fast the thief and murderer," he remarked, "it lets itself go loose. When I have not paid the tax which the State demanded for that protection which I did not want, itself has robbed me; when I have asserted the liberty it presumed to declare, itself has imprisoned me." He again recounted his arrest in Walden, which he also began to write while living at the Pond. "One afternoon, near the end of the first summer," he recalled, "when I went to the village to get a shoe from the cobbler's, I was seized and put into jail, because, as I have elsewhere related, I did not pay a tax to, or recognize the authority of, the State which buys and sells men, women, and children, like cattle at the door of its senate-house...I might have resisted forcibly with more or less effect, might have run "amok" against society; but I preferred that society should run " amok" against me, it being the desperate party. However, I was released the next day, obtained my mended shoe, and returned to the woods in season to get my dinner of huckleberries on Fair Haven Hill." Thoreau's most extensive rendition of what he sardonically termed "My Prisons" was included in an essay that was re-titled "Civil Disobedience" after his death, but which he published in 1849 as "Resistance to Civil Government: A Lecture delivered in 1847." Here, as in his other iterations, he was careful not to pretend himself a hero for having spent a night in jail. Instead, he focused more on his larger purpose, which was to affirm what he saw as the obligation to sever ties with government in light of the ongoing horror of slavery and the U.S-Mexican War (1846-1848). And just as he acknowledged in Walden that he "might have forcibly resisted" arrest, he maintained in "Resistance to Civil Government" that it is sometimes legitimate to take violent action to prevent more general suffering. In the first place, Thoreau argued, paying taxes within the context of unjust war and slavery is itself a belligerent act because it "enable[s] the State to commit violence and shed innocent blood." Moreover, in the face of such mayhem, merely withdrawing support is insufficient since it fuels the violence inherent in ignoring the dictates of conscience: "But even suppose blood should flow. Is there not a sort of blood shed when the conscience is wounded? Through this wound a man's real manhood and immortality flow out, and he bleeds to an everlasting death. I see this blood flowing now." He had, at this point, refused to pay his poll tax for approximately six years, which suggests that his non-payment of the poll tax dates from around the time of his resignation from First Parish Church in Concord in 1841. At that time, he claimed in "Resistance," "the State met me in behalf of the Church, and commanded me to pay a certain sum toward the support of a clergyman whose preaching my father attended, but never I myself. "Pay," it said, "or be locked up in the jail." I declined to pay...However, at the request of the selectmen, I condescended to make some such statement as this in writing: — '- Know all men by these presents, that I, Henry Thoreau, do not wish to be regarded as a member of any incorporated society which I have not joined.' This I gave to the town clerk; and he has it." In fact, what Thoreau submitted to the clerk was not quite so sweeping. "Mr. Clerk," he addressed his statement, "I do not wish to be considered a member of the First Parish in this town."

|