Visit Boston's African Meeting House, built in 1806. Walk the Black Heritage Trail. Visit the Bostonian Society and Old State House Museum. |

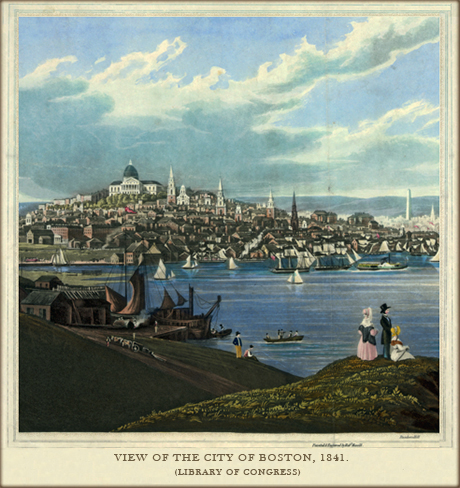

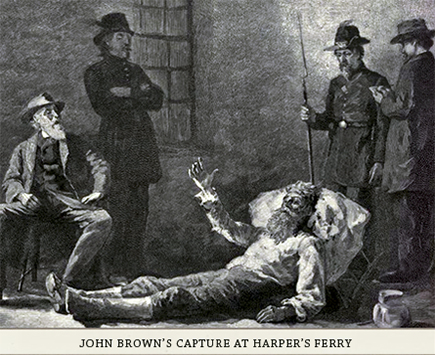

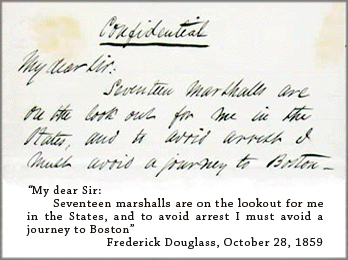

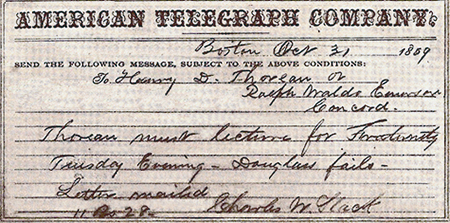

BostonAfter Thoreau was born in Concord in 1817, the family moved first to Chelmsford from 1818 to 1821, then to Boston, where the Thoreaus lived at 4 Pinckney Street until they returned to Concord in 1823. He traveled to the city frequently throughout his life, sometimes in connection with his work in the family pencil business, and sometimes on his way to other destinations, but often as a participant in the vibrant literary, scientific, cultural, and political scene that distinguished Boston among American cities in the decades before the Civil War. His Boston lectures include "Reform and the Reformers," in two parts, on March 10, 1844; "Economy" on March 22, 1852; "Life in the Woods" on April 6, 1852; "Life Misspent" on October 9, 1859; and "The Character and Actions of Captain John Brown" on November 1, 1859. Thoreau's 1844 lecture, his first at a lyceum outside of Concord, was part of a series of talks on political reform held at Amory Hall. The talks he gave in 1852 derived from his two-year experiment in living at Walden Pond. Like these earlier lectures, "Life Misspent," which he delivered elsewhere under the titles, "Getting a Living" and "What Shall It Profit," evolved over months of reflection and revision. In contrast, Thoreau composed his lecture on John Brown in just over a week, immediately after learning that Brown had led a raid on the federal arsenal at Harper's Ferry, Virginia that ended with his capture on October 19, 1859. The lecture evolved in the midst of the national uproar sparked by what was widely seen as the insanity of Brown's attempt to commandeer the weapons stored at Harper's Ferry to spark what he dreamed would become a general war against slavery. Having been impressed when Brown came to Concord to raise funds for his abolitionist crusade, Thoreau was outraged by the failure of the anti-slavery forces to defend Brown's actions. After pouring pages of angry insight into his journal, he sent word around Concord that he would speak about Brown in the vestry of the First Parish Church on October 30. Even Brown's most ardent supporters, such as Franklin Sanborn, who had helped to raise funds to arm the tiny band of militants who served under Brown's command, advised Thoreau to remain silent until the furor over the events at Harper's Ferry died down. Characteristically, Thoreau dismissed this caution, replying to the Concord Abolitionist Committee that its members had misunderstood his message: "I did not send to you for advice, but to announce that I am to speak." Thoreau's Concord lecture, which he titled in a letter, "The character of Captain Brown, now in the clutches of the slaveholder," immediately led to an urgent invitation to speak in Boston under circumstances that reflected the drama of the hour. Frederick Douglass had been scheduled to give the fifth of the Fraternity Lectures at Tremont Temple, one of the largest and most significant venues on the national abolitionist circuit. But when news of Brown's raid reached federal officials, they moved to arrest Douglass, who had played no part, on the suspicion that he had abetted the scheme. Upon learning that Douglass had fled to Canada—with seventeen marshals at his heels—lecture organizer Charles Stack turned to Thoreau to fill the vacancy. Thoreau reportedly opened his lecture before a crowd of approximately 2,500 by announcing, "The reason Frederick Douglass is not here is the reason I am."

Learn more about Thoreau's Fraternity Lecture at the American Antiquarian Society.

|